Before the arrival of the Spanish to the Caribbean islands, people had been living in the Americas for between 13,000 and 15,000 years, after crossing the Beringia land bridge, which was formed between northeastern Siberia and western Alaska due to the lowering of sea levels during the Last Glacial Period. These populations expanded south and rapidly spread throughout North and South America. Distinct cultures, such as the Clovis culture, began to develop as these early Americans probed further south and began settling down. A hallmark associated with the Clovis people, which began to appear around 11,500 years ago, was their use of the distinctly shaped, fluted-stone spear point, known today as the Clovis Point.

Throughout the millennia preceding 1492, several cultures, civilisations and empires sprang up throughout North America, Mesoamerica, and South America. Perhaps the three greatest and well known of which were the Maya, Aztec, and Inca. What was the difference between these groups of people? Once again, the Eurocentric view of history has blighted the modern understanding of non-European history. Too often the history of the Pre-Columbian American civilisations are only considered in so far as they relate to the Spanish conquest of the Americas. Much is discussed about ritualistic human sacrifice and smallpox, but not so much about anything else, consequently leading these great and proud civilisations to blend together.

The reality could not be further from the truth; two continents with thousands of years of habitation can never, and should never, be boiled down to several decades of European expansion and colonialism. The societies that existed before the arrival of the conquistadors were extraordinarily complex and, of course, produced their own histories. They were also completely unique and distinct from one another; the Aztecs and Inca were as different from one another as the Ancient Egyptians were from Tang China.

The Mayan civilisation began in the Yucatan Peninsula around four thousand years ago and were subsistence farmers for much of their history; but their great cities had mostly disappeared by the time that the Spanish even arrived upon their shores. The Aztec Empire was born from a triple alliance of city-states in Central Mexico, and they built up an unbelievable capital city in Tenochtitlan. Unlike the Maya, the Aztecs were only around for one hundred years before the Spanish and their allies wiped them out. Finally, the Inca were from South America, not Mesoamerica like the Maya and the Aztecs, and they lived almost entirely in the western coastal Andean mountain range for over a century before Francisco Pizarro conquered them.

The Sources

For the most part, the archaeological work of these civilisations has unearthed much information, but the Maya and the Aztec also left written accounts, both of which used pictograph writing. Much of the Mayan texts that remain contain dynastic records, meaning that they recorded their own history. The reason that so much Mayan writing has been preserved is because they wrote a lot of it down on surfaces such as ceramics and temple walls, and even on staircases.

Aztec scripture has proven a little more problematic to decipher as they were not around long enough to produce a fully detailed writing system. From the codices that remain, it is clear that they appreciated the skill of writing; but unfortunately, the Spanish burned almost all of their texts. Most of what we know about the Aztecs comes from the first-hand accounts of the Spaniards who interacted with them.

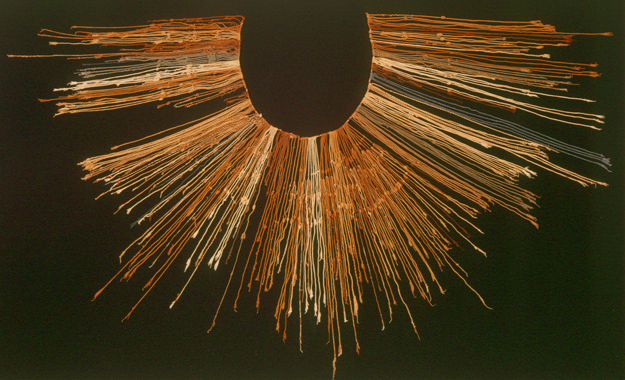

The Inca, themselves, never created a system of writing that is familiar to us. Instead, they used a collection of knotted cords of differing lengths and colours called a khipu. These khipu were used for different types of numerical data collection, such as: measuring taxes; recording census’; and keeping track of dates and events. Rather than writing things down, the Inca relied on oral tradition, and as such, most of the information that we have today about the Inca comes from, again, the Spanish, and knowledge that has been passed down orally.

Spanish accounts of the peoples that they encountered in the New World are likely to portray the native Americans in either a negative or exoticized manner, but unfortunately these biased records are the best that there is to go on.

The Hydraulic Engineers

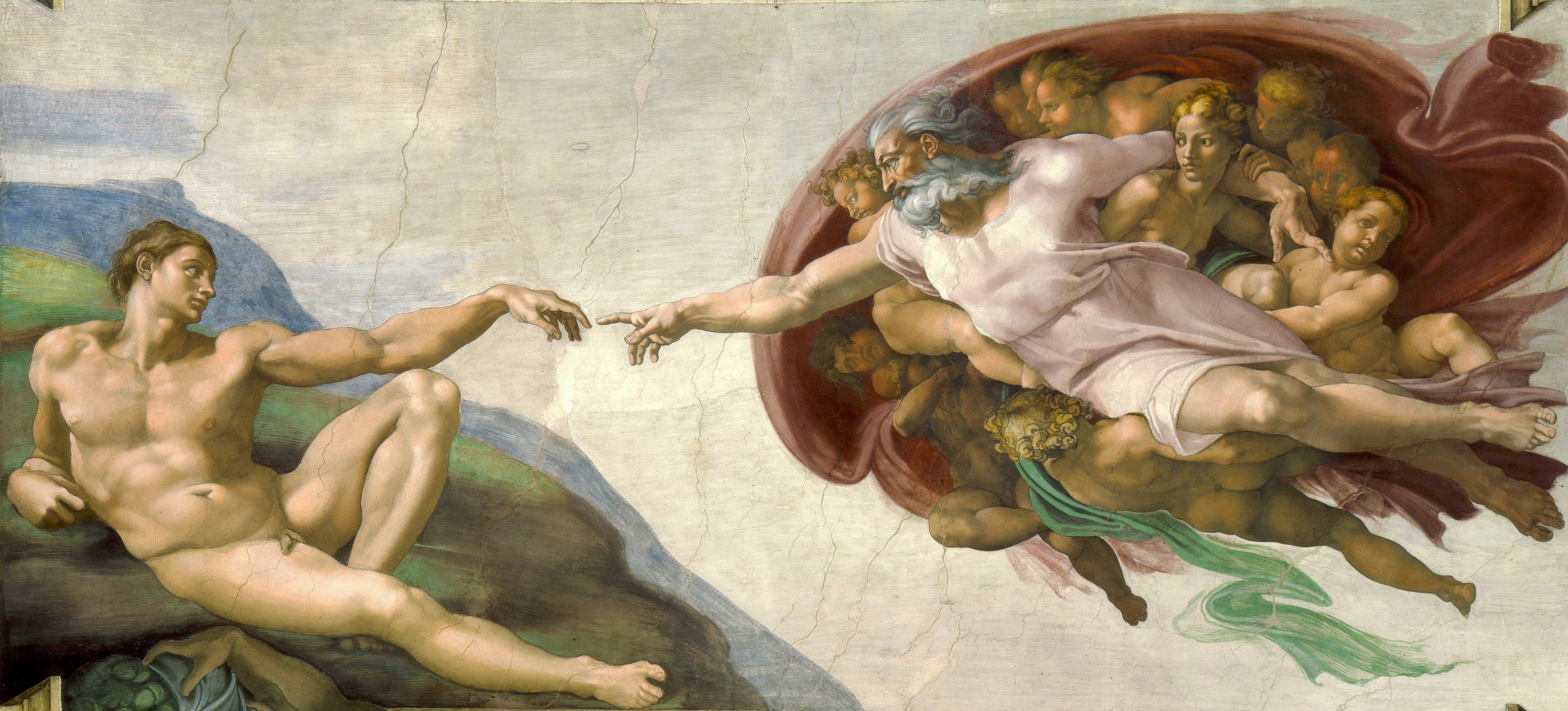

The Aztecs (1428 – 1521) and the Inca (1438 – 1533) were relatively late civilisations, as they only came along in the centuries immediately preceding the arrival of the conquistadors. To put this into perspective, these two civilisations were contemporaneous with the European Renaissance.

The Maya, however, were ancient; but not quite as ancient as the Olmec civilisation, the first civilisation in all of Mesoamerica, which flourished for nearly two thousand years between 1500 BCE and 400 CE. An abundance of Olmec art and statues have survived, and yet the Olmecs still remain a deeply mysterious people. Slightly less old than the Olmecs is the central Mexican city of Teotihuacan, which is similarly shrouded in mystery, although we do know that this was the first true metropolis of North America. The most famous building of this fabulously designed city is the Pyramid of the Sun, which was built around the turn of the third century CE. Aside from the structural remains of the city, little else is known of this wonder; not even who lived there. However, the presence of shattered and burned statues points to evidence of a popular uprising against the ruling class near the end of the city’s life. The city of Teotihuacan most likely laid the groundwork for and influenced the subsequent Mesoamerican cultures as we understand them, including the Maya.

Agriculture in the Yucatan Peninsula developed during the second millennium BCE, and by around 500 BCE large urban areas were beginning to appear. In the centuries following 250 CE, the Maya really began to hit their stride: building colossal monuments covered in writing; connecting cities through trade; and began to demonstrate significant intellectual and artistic development. The leaps forward made by the Maya during this golden age was made more impressive because the Yucatan Peninsula was not a hospitable area for humans to live. The Peninsula is a karst plain with a bedrock of limestone. The soils are poor, and the water table is too low to excavate without modern drilling equipment. On top of this, there are not many rivers and the rainfall is seasonal, with torrential downpours during the unpredictable wet season and the area often suffers long dry seasons. These geological and meteorological problems make it nearly impossible to farm conventionally. Instead, the Maya practised slash and burn agriculture, where the farmer would slash down vegetation and then burn it to infuse the soil with enough nutrients to sustain crops for a few years, before moving onto another plot of land and allowing the old forestry time to regrow.

Despite these challenges (or perhaps because of them) the Mayans built a remarkably complex culture in one of the world’s least hospitable regions, and they could never have done so without water management. Take Tikal for example. This was one of the major Mayan centres that still contains over three thousand structures in its 16 square kilometre footprint. The city, however, entirely lacked a natural supply of water. To supply water to the 60,000 people who lived and worked in Tikal, the Mayans created reservoirs. The reservoirs of Tikal are only one solution, but a diverse environment requires diverse answers to water shortages. At Edzna they built cisterns to capture rainwater and dug canals to connect water reservoirs to the central ceremonial complex. Again, at the city Palenque, in the lowlands Chiapas in modern Mexico, the Mayan engineers applied a local solution to a local problem, building aqueducts, dams, channels and drains to control the flooding caused by the streams that fed the city.

Much like the recurrent seasons that provided the Maya with precious water, their religion was also heavily cyclical. Mayans believed that the world went through cycles of creation and destruction, and that most of their deities were likewise bound to the cyclicity of the eternal universe. Consequently, the Mayans thought that no beginning or end was definite, and that when someone died, they went on a journey through the underworld and the heavens before being reincarnated back on earth. This helps to explain why they were so comfortable with the practice of human sacrifice, which was predominantly a priestly measure to delay the rebirth of the world and the collapse of the world as they knew it.

Whilst their mythology may have emphasised that nothing ever truly ended, history, with a little help from climate change, had other plans for the Mayan civilisation. A series of droughts led to a gradual decline of Mayan culture in the southern Yucatan Peninsula. Cities were mostly abandoned due to a likely mix of too many people and too little water, and the Maya began to recede into the northern Yucatan where water was more reliably available. Cities like Chichen Itza and Mayapan began to grow and develop into the dominant urban centres of the later Mayan civilisation. However, even these cities gave way in the twelfth and fifteenth centuries respectively, and so there was little left of the Mayan culture to conquer by the time that the Spanish arrived.

The City Beyond Dreams

To the northwest of where the Mayan people called home was land that the Aztecs inhabited. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, a series of independent city-states began to appear around the Texcoco Lake Valley in what is today central Mexica. One such group of people, the Mexica, as they called themselves, settled into an island in the middle of the lake and founded the city of Tenochtitlan in 1325. Both the city and its culture began to spread over the next century, physically as the Mexica built artificial islands, and ideologically and commercially as trade with their neighbours increased and its religious influence grew along those trade routes.

In 1428, the Mexica formed an alliance with two nearby other peoples, forming the Aztec Empire which quickly began to expand its territory and conquer their neighbours. They achieved this relatively easily as their armies were large and the warriors were extremely skilled. Not only did the Aztecs conscript every adult male for warring, but they also absorbed the warriors from conquered territories as well as their allies into the Aztec army.

Although the Aztec venture had begun as an alliance of three equal parties, the Mexica people fast became the more equal of the three and took more of the spoils for themselves. While conquering and expanding deeper into southern Mexico, the Mexica city, Tenochtitlan, now capital of the Empire, became increasingly splendid. As an immensely wealthy city based within an island, much like Venice, Tenochtitlan was dotted with canals and huge places of worship, as well as botanical gardens and impressive zoos. At its zenith, it is estimated that the Aztec capital city would have been home to between 200,000 and 400,000 inhabitants, placing it amongst the largest cities of the time; and compared to the cities of Europe, only Paris, Venice and Constantinople may have rivalled it. Tenochtitlan was so massive and splendid that one Spanish soldier, Bernal Diaz del Castillo, wrote of the city:

“When we saw so many cities and villages built in the water and other great towns on dry land we were amazed and said that it was like the enchantments… on account of the great towers and cues and buildings rising from the water, and all built of masonry. And some of our soldiers even asked whether the things that we saw were not a dream?… I do not know how to describe it, seeing things as we did that had never been heard of or seen before, not even dreamed about.”

Tenochtitlan was meticulously clean, free of pestilence, and well organised. The canal system was so intricate that most of the city could easily be traversed by canoe, and both these canals and the streets were cleaned every day by the forerunners of today’s garbage men. One thousand men were employed to clean the streets and “Garbage Boats” went from house to house carrying away refuse and human waste to be properly disposed of.

If living in this splendid city was not enough of a boon, the people of Tenochtitlan could also be entertained through sports. The Aztecs played a game that their Mayan and other Mesoamerican neighbours are known for, called ōllamalitzli. The rules of the game are long forgotten but judging from a descendent game of ōllamalitzli, the aim was likely to keep a rubber ball in play as long as possible, without letting it touch the ground. The game had important ritualistic and mythological aspects, and major ballgames would often have been held as ritual events. Large scale gambling would accompany the games that were staged frequently in the different city wards and markets. One early Spanish chronicler, Diego Duran, even said that “these wretches… sold their children in order to bet and even staked themselves and became slaves.”

The Empire in the Sky

On the edge of western South America, wedged between Earth’s driest desert, largest rainforest and second highest mountain range laid an expansive empire. The Inca, through ingenious engineering and strict central planning forged one of the world’s most unusual empires. Covering a massive two million square kilometres with a population of over ten million and an innumerable amount of ethnic groups and languages, the Incan Empire was the largest polity of the Pre-Columbian Americas. Incredibly, they achieved this without a written language, money, or even the wheel.

The Andean cultures developed in near isolation, so many of the things that were crucially vital to the Old World, such as the wheel and draft animals capable of pulling great weight were absent. Similarly, iron and steel were unknown to these cultures whilst gold, silver and bronze were masterfully worked.

The mighty Incan Empire exploded from the humble beginnings of one small kingdom, Cusco, located high in the mountains of modern Peru. The Kingdom of Cusco was founded under the leadership of Manco Capac at the beginning of the thirteenth century, and the eighth king, Viracocha declared, upon taking the throne, that he would “conquer half the world.” He never did, but his son, Cusi Yupanqui, did; or at least half of the world known to them.

Cusi Yupanqui rose to power in the early fifteenth century. He was not the first in line to the throne of the Cusco kingdom, but after Cusco was besieged by their Chanka enemy, Viracocha, along with two of his sons, fled the city, and it was Cusi Yupanqui who organised a successful defence, winning the crown for himself in doing so. Before his reign, the Kingdom of Cusco held a small amount of territory around the city. He and his son, Topa Yupanqui, stretched their kingdom from present day Bolivia to Ecuador and Cusi Yupanqui adopted the name Pachacuti, or Earthshaker.

Using spies, Pachacuti would assess the military strength and wealth of other states in the region. After collecting this information, he would send envoys to the leaders of these states and attempt to persuade them to join his expanding empire. He promised that they would be allowed to keep their positions and only grow ever more powerful if they accepted his proposal and submit to his supremacy peacefully. If these leaders accepted the terms proposed to them, then their heirs would be sent to the Royal Court in Cusco, whereupon they were educated in an Incan fashion and raised to be ideal Incan leaders. Once their education was complete, they were sent home to their lands to rule in a thoroughly Incan manner. If, however, the terms were rejected, the huge multi-ethnic Incan armies built by Pachacuti were deployed to crush and subjugate.

Emperor Pachacuti reorganised the Kingdom of Cusco and the Incan Empire using a federalist system. He split his empire into four parts, called suyus, each managed by provincial governors who reported directly to the central government based in Cusco. The city itself was also transformed into a suitable Imperial City and centre for the new empire. The city was paved with perfectly cut stone and from its centre spread vast highways linking all the suyus. Just as all roads led to Rome within their empire, all roads led to Cusco within the Incan Empire. Along with these enormous infrastructure projects, Pachacuti also initiated the construction of huge royal estates and palaces, the most famous of which is Machu Pichu located 2,430 metres above sea level.

The rapid growth of this Andean empire was breath-taking, made all the more impressive by the fact that the Inca attempted to integrate conquered peoples into their empire rather than setting up mostly independent tributary states like that other great contemporary Pre-Columbian American empire, the Aztecs, had done. The Inca had utilised both their soft and hard power to expand their reach down the spine of South America, and in less than one hundred years had created the greatest empire in the Americas.

The Rest is History

Enjoy this? Then check out the rest of the series in the links below:

- The Wise Man’s Journey

- The Agricultural Revolution

- Early Settlement

- The Indus Valley Civilisation

- Mesopotamia

- Ancient Egypt

- West Vs East

- Hinduism, Buddhism & Ashoka the Great

- Ancient China

- Alexander…the Great?

- The Silk Road & Ancient Trade

- The Roman Republic. Or was it Empire?

- The Covenant & the Messiah

- Fall of the Roman Empire… Rise of the Byzantine Empire

- The Rise of Islam

- The Dark Ages

- The Cross and the Crescent – The Crusades

- Medieval Africa and Islam

- The Mongols

- Black Death & Disease Black Death & Disease

- Indian Ocean Trade

- The Venetians & The Ottomans: A Convenient Relationship

- Rise of the Bear: Early Russia

- The Renaissance

- The Age of Discovery